A LABOR DAY WEEKEND TARIFF RULING FROM THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT—A SEPARATION OF POWERS SHOWDOWN GOES TO SCOTUS

INTRODUCTION AND ANALYSIS

On Friday, August 30th, a divided federal appeals court issued a ruling on the majority of the President’s tariffs imposed to address various declared emergencies from trade imbalance, fentanyl ingress into the United States, as well as a manufacturing crisis that directly affects national security and economic health. The judges split 7-4 in favor of striking down the tariffs on two main issues. The Opinion may be viewed here.

- Tariffs are taxes at their core, and the taxing authority lies with Congress;

- The International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) authorizes the Chief Executive to “regulate” commerce; however, in interpreting the statutory wording, the Court held that the absence of the terms “tariff” or “duty,” among other language, was evidence that Congress did not intend to delegate this authority to the President.

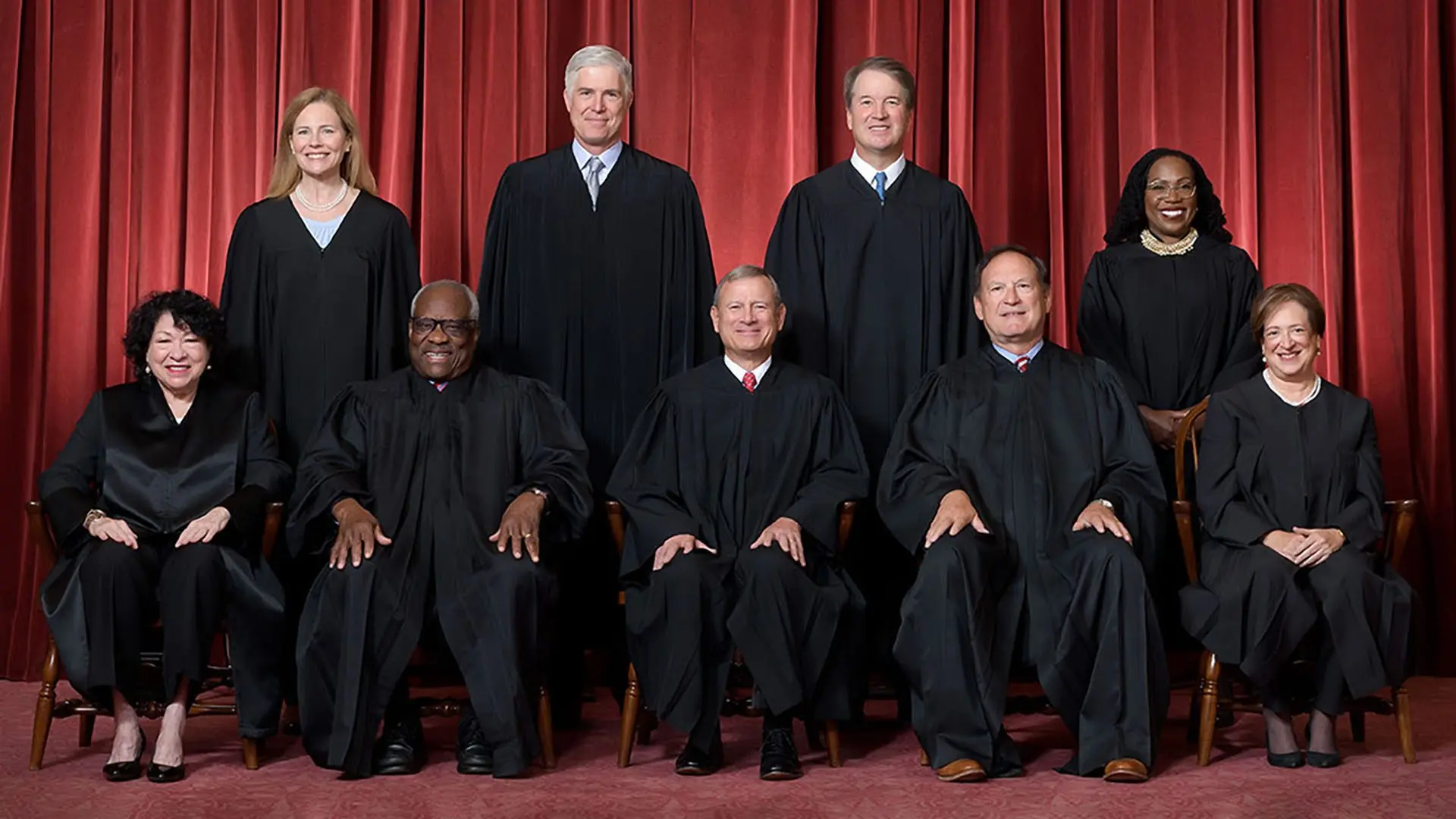

I will discuss the dissenting views below. In his Executive Orders, President Trump cited the IEEPA as well as his inherent Article II authority. Congress delegated to the President the power to so declare such emergencies. Here, the Court found that no such emergency existed, and this sets up whether this question may even be asked by the Judiciary. I predict that the Supreme Court will grant certiorari and perhaps stay the ruling in the interim. The rulings mandate has been stayed until October 14th to allow such appeal. This is a true case of first impression, and the interpretation of the statute as well as a President’s emergency power will be established for future guidance.

SOME BACKGROUND

The IEEPA is discussed, as well as the use of the Act by the President, at Congress.gov, in part, as follows.

“On April 2, 2025, President Donald J. Trump declared a national emergency and announced that he would be imposing a 10% tariff on most imports to the United States and additional duties on certain trading partners. President Trump cited the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) (50 U.S.C. §§1701 et seq.) as his underlying authority. IEEPA may be used “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States,” if the President declares a national emergency under the National Emergencies Act (NEA) (50 U.S.C. §§1601 et seq.) with respect to that threat. IEEPA authorizes the President to “regulate” a variety of international economic transactions, including imports. Whether “regulate” includes the power to impose a tariff, and the scale and scope of what tariffs might be authorized under the statute, are open questions, as no President has previously used IEEPA to impose tariffs.”

The Committee for a Responsible Budget has analyzed the revenue generated by such tariffs, which, if allowed to proceed, may generate significant revenue during the period of this Presidential term;

- Monthly tariff revenue has more than tripled, from $7 billion late last year to about $25 billion in July, and is on course to rise substantially in the coming months.

- The new tariffs introduced by the current Trump Administration will generate an estimated $1.3 trillion of net new revenue through the end of his term and $2.8 trillion through 2034, before accounting for economic effects—about $600 billion more than the tariffs in effect as of May.

THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT HOLDING EXPLAINED IN SNAPSHOTS OF THE OPINION

The scope of the issues was addressed as follows:

“We are not addressing whether the President’s actions should have been taken as a matter of policy. Nor are we deciding whether IEEPA authorizes any tariffs at all. Rather, the only issue we resolve on appeal is whether the Trafficking Tariffs and Reciprocal Tariffs imposed by the Challenged Executive Orders are authorized by IEEPA. We conclude they are not.”

They see the tariff power as almost exclusively the province of Congress, which, in the view of the majority, did not delegate such broad authority in the IEEPA:

“IEEPA authorizes the President to take certain actions in response to a declared national emergency arising from an ‘unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.’ 50 U.S.C. § 1701(a). Upon the declaration of such an emergency, IEEPA authorizes the President to: investigate, block during the pendency of an investigation, regulate, direct and compel, nullify, void, prevent, or prohibit any acquisition, holding, withholding, use, transfer, withdrawal, transportation, importation, or exportation of, or dealing in, or exercising any right, power, or privilege with respect to, or transactions involving, any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest by any person, or with respect to any property subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. 50 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(1)(B). The statute bestows significant authority on the President to undertake a number of actions in response to a declared national emergency, but none of these actions explicitly include the power to impose tariffs, duties, or the power to tax. The Government locates that authority within the term ‘regulate . . . importation,’ but it is far from plain that ‘regulate . . . importation,’ in this context, includes the power to impose the tariffs at issue in this case.”

They explained the historical basis for the holding:

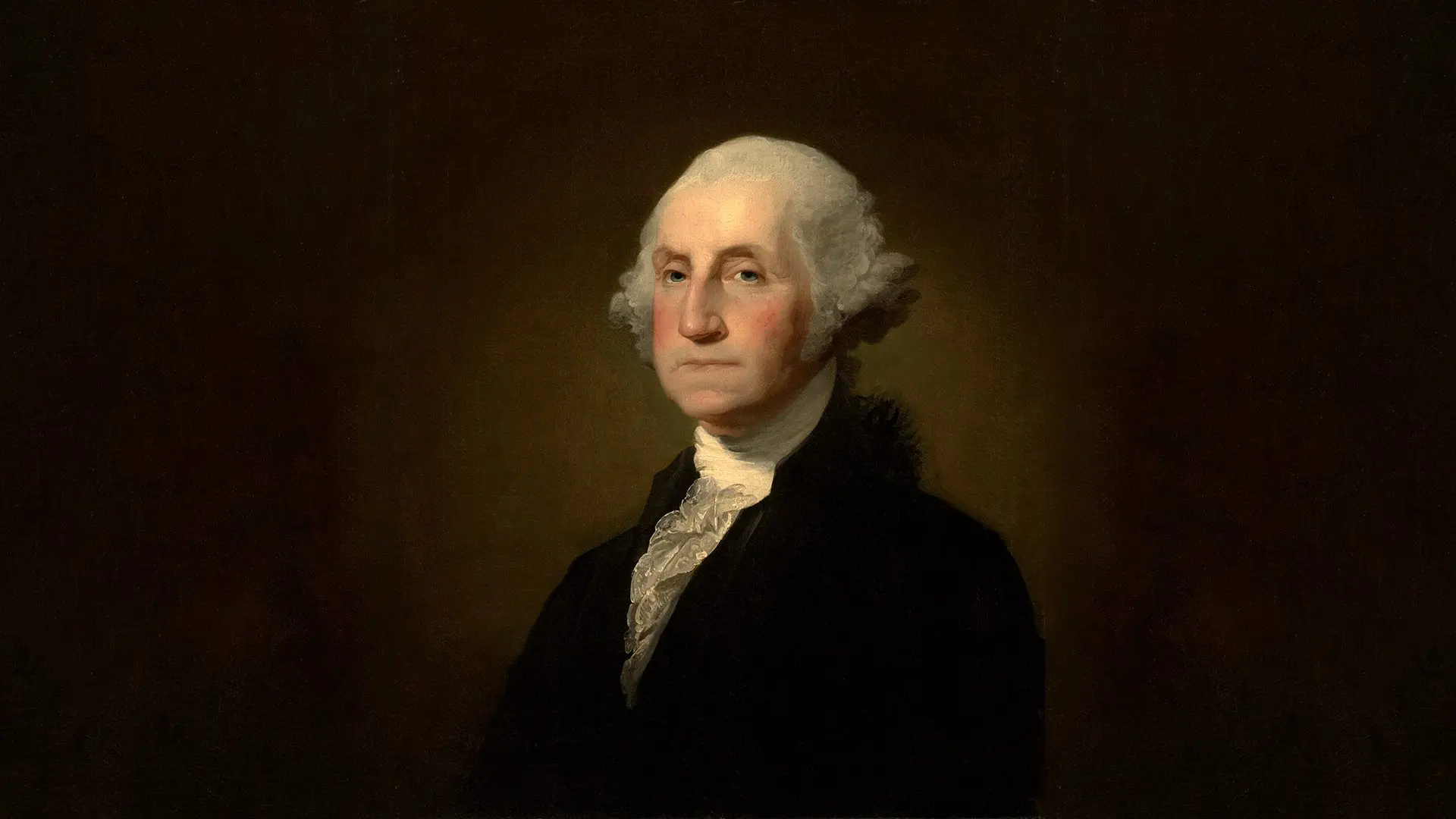

“The Constitution grants Congress the power to ‘lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises’ and to ‘regulate Commerce with foreign Nations.’ U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 1, 3. Tariffs are a tax, and the Framers of the Constitution expressly contemplated the exclusive grant of taxing power to the legislative branch; when Patrick Henry expressed concern that the President ‘may easily become king,’ James Madison replied that this would not occur because ‘[t]he purse is in the hands of the representatives of the people.’ At the time of the Founding, and for most of the early history of the United States, tariffs were the primary source of revenue for the federal government. Setting tariff policy was thus considered a core Congressional function. In 1913, the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified, granting Congress the ‘power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived.’ U.S. Const. amend. XVI. This ability of Congress to impose a domestic income tax reduced the importance of tariffs as a source of revenue for the federal government.”

The Court did not see in the IEEPA language authorizing such authority to “tax” or “regulate” by the imposition of tariffs;

“IEEPA provides that, after declaring a national emergency pursuant to the NEA (National Emergency Act), the President may ‘investigate, block during the pendency of an investigation, regulate, direct and compel, nullify, void, prevent or prohibit, any . . . importation or exportation of . . . any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest.’ 50 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(1)(B). Notably, IEEPA does not use the words ‘tariffs’ or ‘duties,’ nor any similar terms like ‘customs,’ ‘taxes,’ or ‘imposts.’ IEEPA also does not have a residual clause granting the President powers beyond those which are explicitly listed.

Contrary to the Government’s assertion, the mere authorization to ‘regulate’ does not in and of itself imply the authority to impose tariffs. The power to ‘regulate’ has long been understood to be distinct from the power to ‘tax.’ In fact, the Constitution vests these authorities in Congress separately. U.S. Const. art. I, § 8 cl. 1, 3; see also Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1, 201 (1824) (‘It is, that all duties, imposts, and excises, shall be uniform. In a separate clause of the enumeration, the power to regulate commerce is given, as being entirely distinct from the right to levy taxes and imposts, and as being a new power, not before conferred. The constitution, then, considers these powers as substantive, and distinct from each other.’); Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519, 552, 567 (2012) (holding that the individual mandate provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was a permissible exercise of Congress’s taxing power but exceeded Congress’s power to regulate commerce). While Congress may use its taxing power in a manner that has a regulatory effect the power to tax is not always incident to the power to regulate.”

The four dissenting judges saw it differently, as “regulate” is broadly defined and the president has authority to declare an emergency that does not have to have occurred in a specific time frame—recovering the economy from a declared COVID emergency as well as the other executive order declarations are within his Article II powers.

“We disagree. Definitions of the term ‘regulate’ provide broad understandings of the term’s ordinary meaning: to ‘fix, establish or control; to adjust by rule, method, or established mode; to direct by rule or restriction; to subject to governing principles or laws.’ Black’s Law Dictionary 1156 (5th ed. 1979); see also Webster’s Third New International Dictionary 1913 (1976) (defining ‘regulate’ as ‘to govern or direct according to rule’ and ‘to bring under the control of law or constituted authority’). As the government states in its opening brief, ‘[i]mposing tariffs on imports is clearly a way of ‘control[ling]’ imports (Black’s); ‘govern[ing] or direct[ing]’ them ‘according to rule’ (Webster’s); ‘adjust[ing]’ them ‘by rule, method, or established mode’ (Black’s); or, more generally ‘subject[ing]’ them ‘to governing principles or laws’ (Black’s).’ This straightforward result is supported by the longstanding judicial recognition that taxes are often a species of regulation—specifically aimed at altering conduct.”

The executive orders setting forth the factors supporting such tariffs provided sufficient foundation for this exercise of authority—a key finding by the dissenters.

“Rather, the problems identified in EO ’257 that the present-day goods trade deficits ‘have led to’ are focused on deficiencies in ‘domestic production’ (including deficiencies in ‘the U.S. manufacturing and defense-industrial base’ and to the nation’s making of agricultural products) wholly or partly caused by the purchase of imported goods made abroad in place of domestically made goods. Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries. Id. at 15041. EO ’257 adds: ‘A nation’s ability to produce domestically is the bedrock of its national and economic security.’ And it elaborates further: Permitting [structural] asymmetries [between the United States and its trading partners] to continue is not sustainable in today’s economic and geopolitical environment because of the effect they have on U.S. domestic production. . . Both my first Administration in 2017, and the Biden Administration in 2022, recognized that increasing domestic manufacturing is critical to U.S. national security. . . U.S. production [particularly in certain advanced industrial sectors] could be permanently weakened. . . [B]ecause the United States has supplied so much military equipment to other countries, U.S. stockpiles of military goods are too low to be compatible with U.S. national defense interests. . . In recent years, the vulnerability of the U.S. economy in this respect was exposed both during the COVID–19 pandemic, when Americans had difficulty accessing essential products, as well as when the Houthi rebels later began attacking cargo ships in the Middle East. . . The decline of U.S. manufacturing capacity threatens the U.S. economy in other ways, including through the loss of manufacturing jobs. . .”

CONCLUSION

The imposition of tariffs by Executive Order may be seen as an impermissible exercise in legislation by the President, which is clearly at odds with constitutional design. When Congress does delegate authority to the President, such delegation is strictly construed in consideration of the separation of powers. The Founders felt that such separation was crucial in preventing certain exercises of Presidential authority, which, if unchecked, would be tantamount to a decree from a king—the main evil the Republic was created to prevent. However, a President’s declaration of emergency, which Congress did permit in the context of the IEAA and other enabling legislation, may well be beyond review by the Judiciary in a complex case, or else courts could assume the role of the Executive. We have seen this in the recent cases and “stay” rulings out of the Supreme Court essentially scolding lower courts who indeed assumed such role in preventing immigration enforcement and actions taken to reduce government and claw back DEI waste. The Supreme Court must review this case, as it is not only fascinating, but it will also be exercising its historic role to say fully and finally what the law is.

Mike Imprevento

September 1st, 2025